Fashion is political

It can and should be used to express our might.

Our bodies are vehicles for expression. And yet we’re losing our bodily autonomy; cookies follow us and algorithms lead us. Becoming virtual does a good job of dividing people by making us invisible to each other, and we see the results in the instability of our democracies and the social issues we face.

Our history is one of using our bodies to protest. Our bodies allow us to publicize our views and – quite literally – stand up or sit down against things. What we wear on our bodies protests too. Nowhere has this been seen more publicly recently than in the keffiyehs, a traditional headscarf worn in support of Palestine, and of the many examples of people being arrested, banned, or removed, for showing solidarity with Palestine (or Plasticine) on their clothing.

Yet this right to use our bodies to protest is being systematically targeted and stripped from us. A corrupt media and legal system fails to uphold our rights. And so what happens in the real world – what we see when we walk around, and inhabit the world with our bodies – is more important than ever.

Our clothes are messengers

As we move around the world, as we talk to one another to discuss what is being silenced, what we wear can – and always has – act as our messenger.

Styles are responsive to culture and community. They have been used to visualise status, appropriateness, religion, hobbies, passions, wealth and class, and have both constrained and exploded around gender and sexual freedom.

Regardless of our intentions, our clothes tell a story, and give an insight into the person beneath. They share unspoken communication, a way to be vocal about who we are, what we believe, what we support and who we want. There’s not enough time to hear the desires of everyone we pass on the street. So the way we dress becomes one of our first methods of communication.

Fashion’s history as liberator and oppressor

Fashion’s history is one of both liberation and oppression. Fashion has upheld standards of craft while also imposing exploitation on millions of workers. It’s also come to be one of the highest polluting industries in the world. At the same time, the severity of the things we need to fight for increases. The climate crisis worsens, trans rights are threatened, disability support is stripped, wars intensify, there’s a regression in reproductive rights, racism is still rising, and the cost of living only grows. Fascism is no longer waiting in the wings, but dressed for success.

This makes the choices we make around what we wear inherently political, even without the application of a specific message. So as a messenger and as a culprit, fashion can – and I believe should – be a method we use to talk about the stuff we care about (including fighting fascism).

This isn’t a new notion of course. The marriage between politics and fashion is intertwined, more than simply the application of political messaging. It comes from the significance of the garments themselves: the construction and the stories that shaped their creation, and how pieces have been designed at times to resist oppressions (or to oppress).

Craft has often offered means and resistance, particularly for women. For example:

- The term ‘spinster’ comes from the title given to an unmarried woman able to achieve financial independence for herself through spinning yarn; patriarchy has sought to add its derogatory connotation to these women of skilled, independent means.

- The Mantua is a style of dress where the sleeves and body are cut from one piece of fabric; it was a garment designed and made by women overlooked as a fad by tailors, who dominated the industry. But the Mantua became the key fashion of the time and changed the dynamics of the industry, and gave women the power to work and the independence this offered.

Vivenne’s legacy

Vivienne Westwood took all of this to a new level. Her legacy is of utilising fashion as a protest, with shocking and transgressive ideals responding to political oppression. She mixed elements of bondage and the iconography of sex with outright political messaging. She used clothes as the grounds for political and social commentary and, with music, created a community and subculture that merged the three. Her approach shifted throughout her career, but politics was at the heart of her work.

Fashion has often been integral to marginalised communities, for rebellion but also for safety, showing up in varying ways depending on the time period and the group. Clothes and accessories have offered a way for people to navigate a world made unsafe for them, to signal to others in the community, like green carnations to help gay men identify one another. It can be used to escape from this world; to become fantasy, as much as art does. This is exemplified within practices such as drag and the ballroom.

But more generally, fashion has been used this way to gain freedom from existing ideas of what is appropriate, especially for women. Standards of dress are deeply ingrained within gender ideology, shaped by misogynistic ideas and enforced through access to personal money and independence. So fashion resisted:

- Named after women’s right advocate Amelia Bloomer, the ‘loose gathered trouser’ bloomer gave women the ability to cycle and to move more freely.

- The mini-skirt was a protest against required modesty.

- The bikini was at first a protest against the USA’s testing of nuclear bombs in an area of the Pacific called Bikini Atoll; the triangles of fabric were printed with newspaper articles about the topic but caused headlines mostly due to the lack of modesty of the item, making the garment significant as a longer term protest for women’s bodily autonomy.

Clothes have often been manipulated as false evidence. Satire was used to cast women as vain and give an excuse to withhold rights and comfort, notably through pieces like the corset. The binning of bras turned into ‘the bra burnings’ in which no bras were burnt. The outfits of victims have been used as defence of the perpetrators of abuse against women, she was ‘asking for it’ became a rationale used for sexual assault. This notion of clothing denoting consent causes retaliation and solidarity, something which at times arrives as clothing choices themselves. We saw this in the white dresses of the #MeToo movement. Pieces like the so-called ‘revenge dress’ worn by Princess Diana acted as a protest on a personal scale, but spoke out louder to the wider world.

T-Shirts

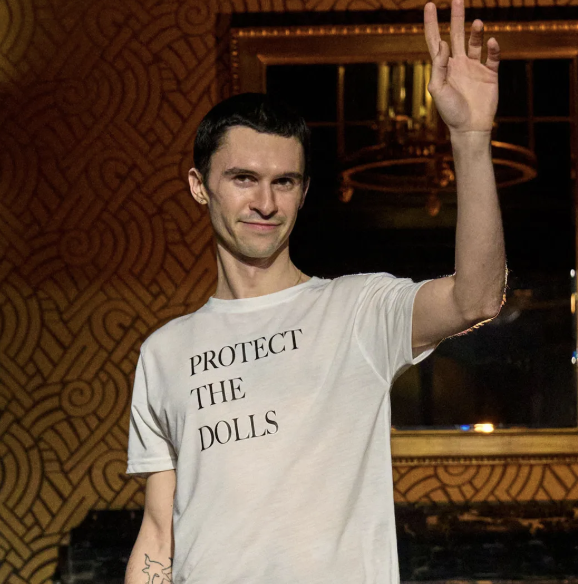

The t-shirt has been a long standing method of signifying interest or community, whether that be in football, band t-shirts etc. Katharine Hamnett created the iconic slogan t-shirt as a carrier for political commentary, something replicated continually by designers.

The rise of brands as our outlet of community, in a world of increasing capitalism, manifests in the rise of the logo t-shirt. But it still remains a key item in political advocacy: protest groups, charities, almost all utilise clothing as a way to spread their message.

Conner Ives recently launched the ‘Protect the Dolls’ t-shirt to protest treatment of trans people in the US. The money raised goes directly to a charity, Trans Lifeline, a trans-led US- based charity that delivers life-saving services.

Recently our friend Ian Bruce hand-painted a watermelon to print onto t-shirts as a fundraiser for Baby Formula to reach Gaza.

Aside from the garments themselves, embellishments are significant in the history of worn protest; badges and pins have a long history of carrying political and social messages, notably red ribbons as a honouring of those suffering from AIDS in the 80s, and black armbands used to protest the Vietnam war. Bodypolitic founders Clare Farrell and Miles Glyn utilised embellishment to politicise clothing, which went on to be an integral part of the visual language of Extinction Rebellion.

Our political might

Whether for style, practicality, ritual, religion, comfort, support, and regardless of our attitudes, most people wear clothes. They offer a collective power often overlooked when demoted into the categories of vanity, or industry. Fashion is political, whether you like it or not.

As protest is silenced, the way in which we express our politics in the clothing we wear is an example of using our voice, of signifying community, of intertwining art with politics and our bodies. We can use these canvases for more than an expression of our personal style – we can resist – for ourselves, and for others less able. So utilise your body as a canvas when you can, to support the things you care for. Our clothes are a means to express our political might.

Elsewhere in Absurdity...

Apart from playing around with a lot of flags (more on that soon) this is our news:

- Come to our Convention! There is a vibrant discussion happening right now about the fate of our nations and neighbourhoods, something that hasn't happened for a while; it feels as if power, agency and the future really are up for grabs. Who do we want to decide on our fate? Us? Come on then...! Come to the Convention on the Fate of Britain, 11th Sept.

- Then go to the The Right to Protest Exhibition! Our Clive has been working with The Museum of Unrest and tonnes of brilliant artists, featuring iconic posters from two of the largest private collections in the UK, and new works by influential designers and artists, including Kennardphillipps, Ackroyd & Harvey, and Stuart Semple, the exhibition is an antidote to the branded more polished and boring world of London Design Festival.