Will the Future Never End? Carney and the New World Order

The Canadian PM's Davos speech names the rupture, but what does it mean for those who can't imagine a better future?

“The future is just more of the past waiting to happen,” writes Fred D’Aguiar, the British author, in his debut novel The Longest Memory.

It tells the story of Whitechapel, a Black slave on a 19th century Virginia plantation, who utters this lamentation as his son is whipped to death. Whitechapel can’t imagine a future in which their collective pain as slaves ends. It is not a failure of imagination – who could possibly accuse a Black slave, even a fictional one, of this? It is more an impasse of imagination: unable to see or feel another future when up against such domination and seemingly unchanging power.

I did not want to say Whitechapel has ‘no hope’. I really do not want to speak about hope. Nor did Mark Carney, Canada’s Prime Minister in his speech to ‘world leaders’ at Davos on Tuesday. Carney used the word ‘hope’ only once, dismissively: as a tactic to fight power, hope has failed.

A stark warning

But that doesn’t mean Carney wasn’t imagining a different future. He spoke, seriously and coherently, about a future that is not just more of the past waiting to happen. His speech has been widely shared and responded to, not least by some of our friends. Carney’s words are a stark warning for the world:

Let me be direct. We are in the midst of a rupture, not a transition. … We know the old order is not coming back. We shouldn’t mourn it. Nostalgia is not a strategy, but we believe that from the fracture we can build something bigger, better, stronger, more just.

He argues world leaders of the “middle powers” (Canada, India, the UK, the EU, Japan, etc) can use this rupture to coordinate and collaborate on issues for a mutual future that is not more of the past, driven by “major” power (US, Russia, China) aggression.

People have latched onto the speech because it is honest and revealing, and says a just and more secure global order may be possible. It isn’t too far away (although with some very major differences, outlined below) in what we’re trying to do at Absurd Intelligence, to help people know and feel that we can – and will – collectively make a better way to live.

Values-based realism

The new phrase used by Carney and other world leaders is “valued-based realism”. It was introduced by the Finnish President Alexander Stubb in 2024, and can be digested in Stubb’s new book The Triangle of Power released last week. Values-based realism is – says Stubb – about a shift in the global order that countries, such as the UK, need to adopt in light a growing ‘Global South’:

On the one hand [The West] should lean on values it has espoused for decades, such as democracy, human rights and international institutions. On the other hand, it needs to understand that global challenges such as climate change, immigration and economic development can’t be solved with like-minded states only. It is not about compromising your values, but realising that in order to make progress you have to compromise some of your interests. At the same time it is about respecting the values and interests of others in the interest of global co-operation.

This, Stubb says, is realism, not hope.

But it depends on what values you’re being real about, doesn’t it? Democracy, human rights, international institutions, good values, right? (Mostly.) But what about the others, implicit in Carney’s speech, propping up the ratchet system that is global neoliberal capitalism?

Replacing the values of consumption and production?

You’ll know if you’ve read this newsletter for a while, that we work to bring David Graeber’s imagination to life, to replace the values of production and consumption with the values of care and freedom.

And we’re very realistic about that.

Our values-based realism is grounded in the values and interests of the people we love in the places where we live. Our neighbourhoods, yes, and also our nations, as flawed as they are. Our work is a love letter to ourselves as a nation of neighbours, who can care for each other’s freedom.

Critically, we are very realistic about the climate and ecological emergencies and impending collapse. So while the form of what we’re doing at Absurd Intelligence feels aligned to what Carney outlined, the content is very different, and it’s worth reflecting on exactly what values Carney is being realistic about…

Just a different kind of business as usual?

In his speech at Davos, Carney was giving us a dose of his values-based realism:

Great powers have begun using economic integration as weapons, tariffs as leverage, financial infrastructure as coercion, supply chains as vulnerabilities to be exploited. You cannot live within the lie of mutual benefit through integration when integration becomes the source of your subordination. … As a result, many countries are drawing the same conclusions that they must develop greater strategic autonomy in energy, food, critical minerals, in finance and supply chains. … A country that cannot feed itself, fuel itself, or defend itself has few options. When the rules no longer protect you, you must protect yourself.

Carney’s answer does not simply offer a warning, but a long list of practical actions that Canada is taking to imagine a future that is not simply more of the past waiting to happen. You can read the whole speech here.

But as the climate diplomacy expert Anne-Sophie Cerisola reminds us, Carney’s “pragmatic” actions and “values-based realism” as Prime Minister of Canada “has meant so far dismantling some of the climate-friendly policies implemented by his predecessor”. As Cerisola continues, Carney has ‘reinvented’ Canada’s fossil-fuel industry “in a way that the 2015 Carney would have probably characterized as increasing the ‘systemic risks’ posed by climate change” that Carney cared about when he was Governor of the Bank of England.

In November, Carney disregarded Canada’s climate laws to sign a new tar sands agreement. Since Carney has been Canadian PM, numerous members of Canada’s Net Zero Advisory Board have resigned, as a direct result of Carney’s climate reversals. And Canada is massively failing on its climate targets. This is his vision of values – strange to think Mark Carney was once UN Special Envoy for Climate Action and Finance...

What kinds of values?

So we need to be careful not to get caught up in the moment: Carney is perhaps the best of a bad Davos bunch, but still in content very much focused on a world-order that is calamitous for humanity, doubling-down on fossil fuels, and on production and consumption as the key values to be ‘real’ about.

For me, Carney’s speech is valuable in form: an invitation to have a national conversation about the kinds of values we want to be ‘real’ about. Do we want to be real or pragmatic about an approach that rolls back on climate action or things that make us healthy? That sounds like Reform’s war on Net Zero, or RFK’s war on protein.

Instead, can we use this moment of rupture to have a national conversation about the values that matter to us? To get past our impasse of imagination, to come together in ways that visualise a new future, one in which we can – and will, and are already – building collectively? And while I imagine those values would include security and safety, it would not be at all costs, or take us back to the fossil-fuel-era.

Okay. But what happens when it feels that as a collective society we’re not far from giving up on the future, and maybe have already?

The neverending cost of living crisis

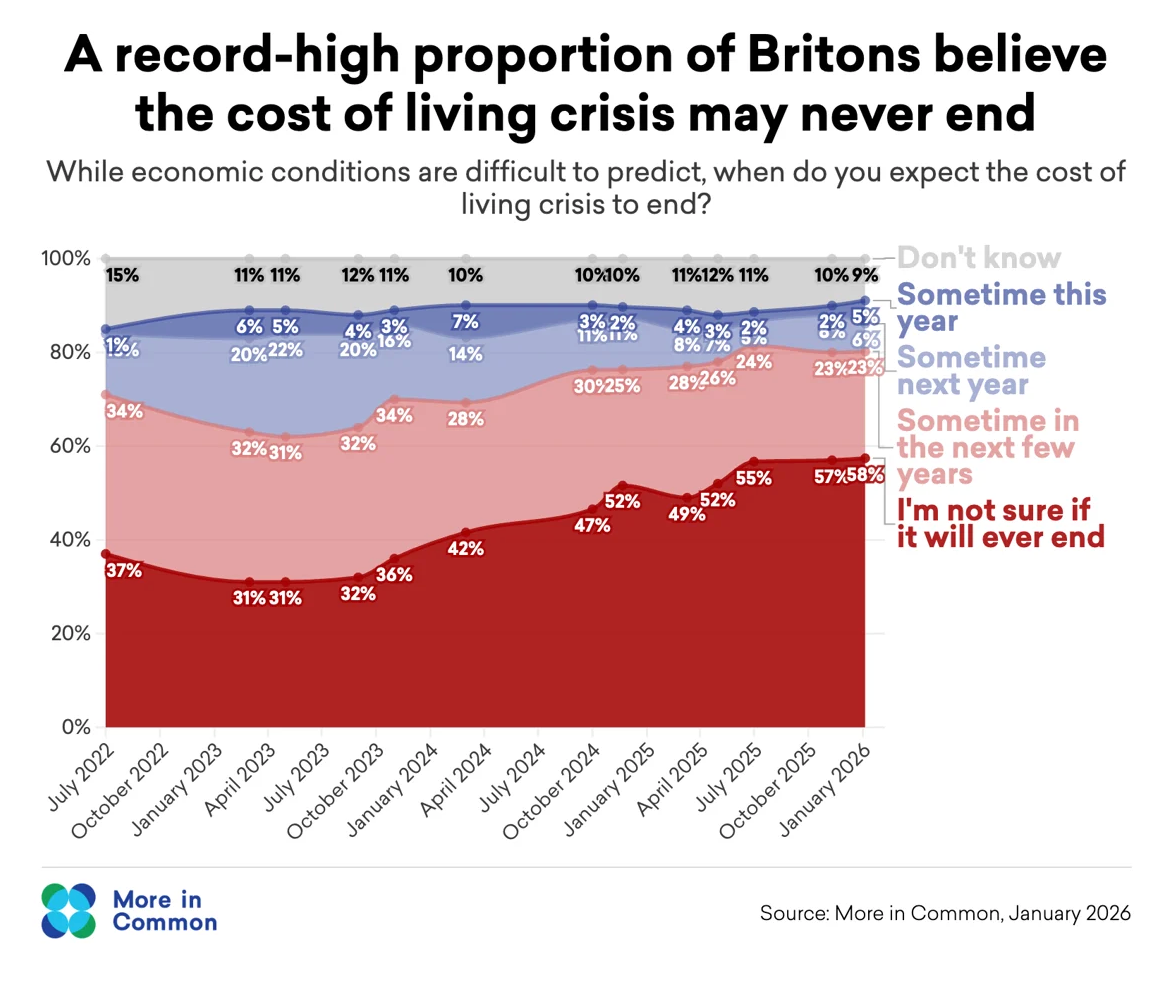

As Stubb’s book was published, and Carney was finalising his speech to Davos, More in Common last week released its polling on the cost-of-living crisis. It put this impasse of imagination on the future pretty starkly. A record 58% of Britons now say that the cost of living crisis may never end:

Britons are not talking about the issue in the abstract – instead they are drawing from their own experiences: 51 per cent say they’re cutting down on luxuries, alongside 46 per cent who are going out less to restaurants, pubs and the cinema. More than a third of Britons (36 per cent) say that they’ve cut down on their electricity or heating usage.

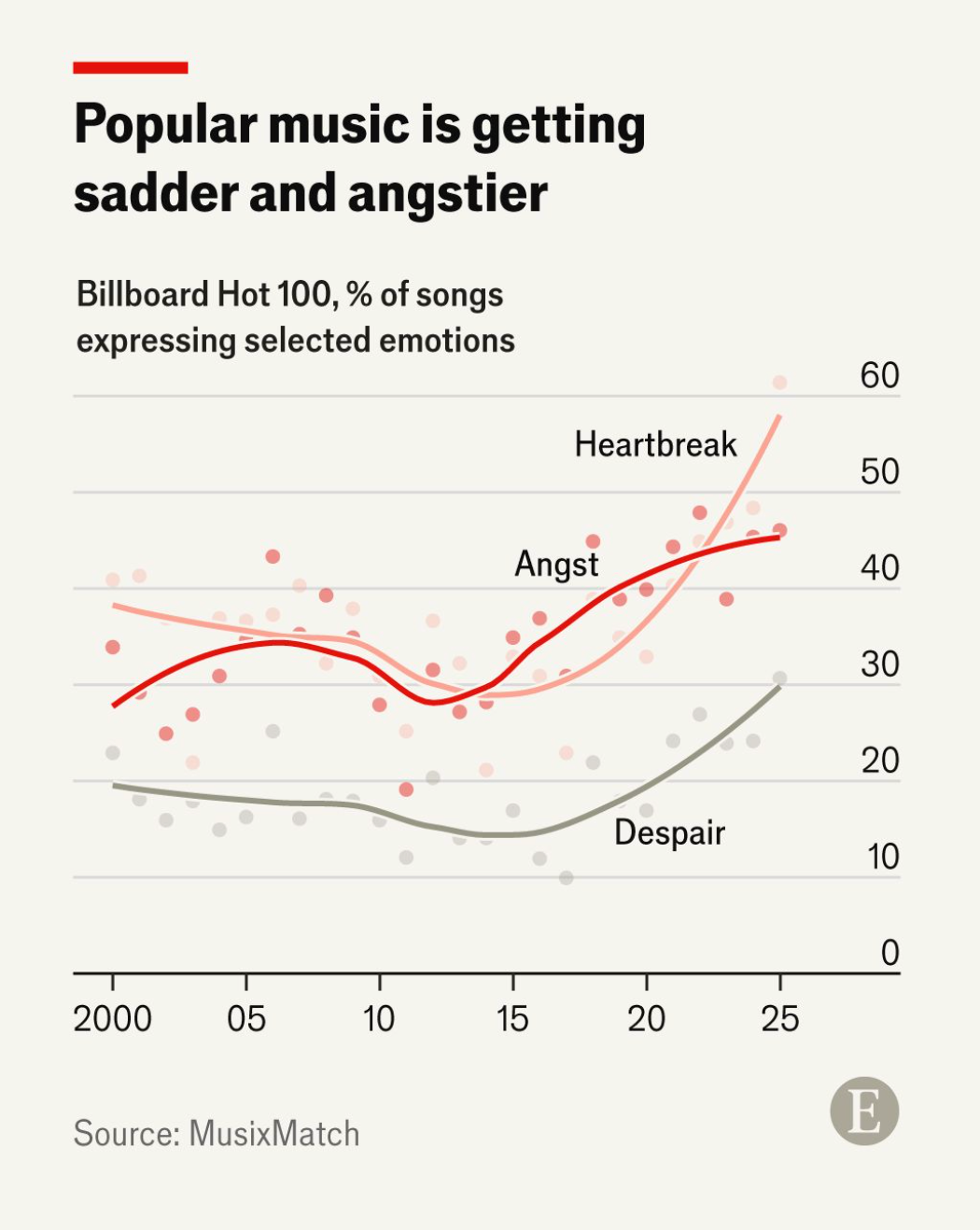

This impasse to imagine a different future has been creeping around us for decades. Young people’s pessimism for the future is growing. As the Economist wrote this week, “melancholy is the mood of the moment.” An analysis of lyrics from the Billboard Top 100 for each week over the past 25 years shows a clear uptick in angst, despair and melancholy since 2015.

Nostalgia is not a strategy

Maybe this January’s social media trend for nostalgic posts of 2016 is a direct result of what has happened since the heady, happy days of 2015? Yet as Carney (and, with more attitude, Louisa Munch) remind us, nostalgia is not a strategy.

The future is in the air, though, of course. This week our colleague David taught an introductory lecture using Jim Dator’s four stories of the future model.

As David says in his post, all models are wrong. Maybe Dator’s is wrong because it assumes that there is always a story of the future. But what if there is no story of the future available, or one that, as Whitechapel says in D’Aguiar’s novel, will never end? And, worse, when they’re right, because the compounding factors of climate and biodiversity collapse – as factually documented in this week’s UK government report “Global Biodiversity Loss, Ecosystem Collapse & National Security” – are getting worse.

What we’re seeing is the increasingly shared belief that tomorrow’s dawn doesn’t exist for us any more, as agents of our own lives.

When I read Jem Bendell’s Deep Adaptation back in 2018, the idea that struck me, and has stayed with me most, summed this up: societal collapse is so psychically painful because it means the end of everything we ever thought we’d contribute to.

As the More in Common polling data put it:

Younger Britons worry about their future and being unable to save for a home. Parents focus on childcare costs and the difficulty of affording small extras for their children … Older Britons often feel they should be feeling more comfortable by now, and that the cost of living crisis has put the retirement they expected out of reach.

The year of hope?

So a lot of people want 2026 to be the year of hope. A future we can imagine being different. This year we’ve already had the launch of ‘Hard Hope’ from the Better Politics Foundation and Hope Works from the former New Labour insider Peter Hyman.

Zack Polanski has framed his campaign messaging around “Making Hope Normal Again.”

But also, as a caveat, Andrew Tate does the same in the Manosphere:

There’s a lot of spitting and choking on Bombay Mix any time hope is discussed here in the office, make of that what you will. What hope definitely is, is a future-oriented concept, that only operates with some sort of acceptance not only of a future, but that the future will be better than now.

The opposite of this is this idea of collapse. Collapse as the breakdown of our existing structures of how we organise ourselves: economically, politically and socially.

But also psychologically. When we have breakdowns, we collapse mentally. Depression and despair are the absence of the idea of a better future.

Countering collapse as a mental state

Is societal collapse then also a mental state? A negative social, political and economic neverendingness of things never getting better?

What we’re doing at Absurd Intelligence, with the Fête of Britain, is to help people know and feel that we can – and will – collectively make a better way to live. It is to begin with the thing that all societies require, which is a sense of the future being available to us, as something we have agency over, in ways that continue society.

It’s the antidote to the feeling that the future will never end; that the future is only more of the past waiting to happen.

It doesn’t mean we have to ‘hope’. It means, instead, we have to get through the impasse of imagination, and do stuff! We have to trust our imagination will work again, and do things that bring what we imagine to life; and give people the chance to experience new ways of being together, not just hear about them.

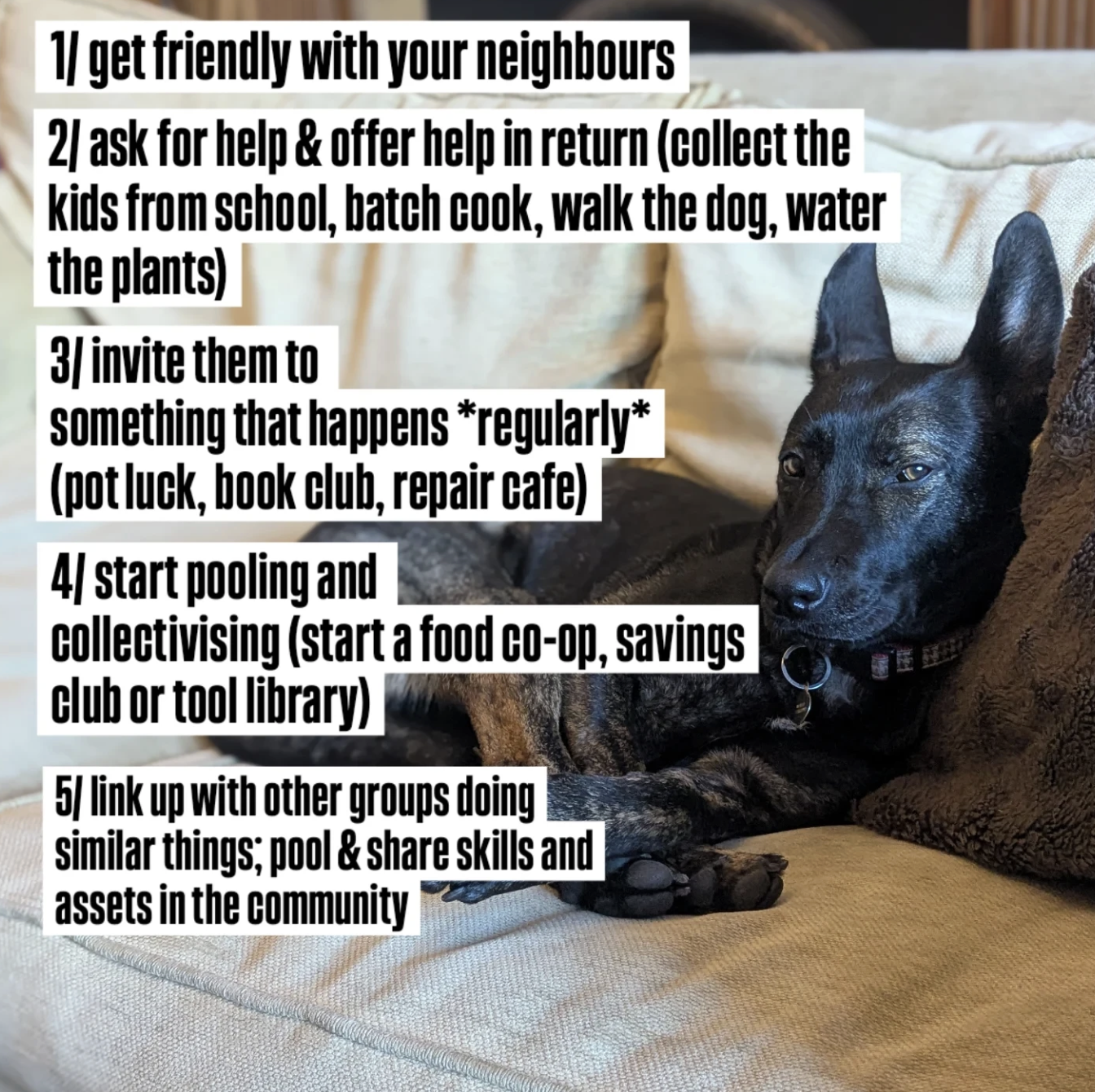

Our friend Gully Bujak from Cooperation Hull puts it really bloody well in her posts here. First thing you can do? “Get friendly with your neighbours.”

Be a good neighbour

Being a good neighbour is our values-based realism, at street level.

Or nationally, as ISWE’s Rich Wilson says here:

Our task is to help our governments and communities wherever we are, rise to the moment. To harness what already works - citizens’ assemblies, deliberative processes, open gov etc. etc. etc. - from niche experiments into governing infrastructure, while the rupture is still open.

That’s what 2026 is for us: a future that hasn’t already happened, and that can be different. That, as Louisa Munch and Amol Rajan discussed on Radio 4, where the politics of nostalgia is outmanoeuvred by a politics of the can, the will, and the are. (Charlie will write about ‘the are’ in a following post.)

Helping us as a nation of neighbours collectively live well together. That, ultimately, is what we want. To contribute, with care and freedom, to a new future. Join us?

Elsewhere in Absurdity...

Welcome back. How’s everyone feeling? I had a time over the break, as mosquitos transferred kangaroo bugs into my bloodstream through their proboscii and cunning proteins. Top that for Christmas misery! On a more positive note:

Most of the team are at the verbatim play In Case of Emergency, about the trial of six medics, including our dear friend Ali – a story of protest, courage, care and hope(!), written by Hard Art friends April de Angelis and directed by Ian Rickson, produced by Empathy Museum / Clare Patey and sound by Genevieve Dawson.

Charlie is at Dash Arts’ We Are Free to Change The World, part 2: Steady.

David started his practice-based Doctorate in Organisational Change at Hult Ashridge, and also attended the memorial service of Professor Sir David Nabarro, one of the architects of the Sustainable Development Goals, crucial in raising public health and nutrition as priorities in multilateral institutions, and regularly brought into lead crisis responses (like ebola outbreaks).

Alex attended UAL’s AKO Storytelling Institute’s afternoon on thinking around inequality and wealth narratives, and met some lovely people.

And we welcome two new members to the team, Diya Sahni and Stella Fass!