Are we flagging yet?

There’s still much to learn from our relationship with national symbols.

Here’s some statements that might sound familiar after the last few months:

Usually it’s hard to get young people interested, but this flags thing has really changed things.

I see people out there who are not political in any way whatsoever, but they feel that protesting is the only way that they will get their voices heard.

These protests are about us remembering who we are.

It’s not about protecting our culture; it is more about those that don’t want you to have a culture.

Those statements were all made in 2013 and 2014, drawn from protesters following intense riots and public disorder in Northern Ireland after Belfast City Council voted to fly the Union (Jack) flag not every day, as they always had, but only on 18 designated days a year.

Unionist and particularly Loyalist communities responded with hurt and anger to the decision, led by the Alliance Party. They saw removing the flag from always flying on the council building as the final straw in the progress towards a ‘new’ Northern Ireland. Those communities felt the Republican agenda to reunify North and South was winning, and it would eradicate the culture, politics and history of those in Northern Ireland who felt British. Here are a few more statements:

They pick, pick, pick away at our culture until all we are left with is scraps.

These people feel that their identity and what they represent is being stripped away, piece by piece, and they can do absolutely nothing about it.

There is a real perception that they are being left behind, and the media are ignoring their arguments.

The symbols are really important … They are a tangible illustration that you exist.

Protests included road blocks (Just Stop Oil weren’t the first), attacks on political offices and even Alliance Party members. For those who have firsthand experience of living in Northern Ireland (and we don’t – here’s a useful backgrounder) the protests may not have been a surprise. Since the 1998 Belfast Good Friday agreement, “flags have come to play a significant part in the maintenance of the conflict and are the source of ongoing controversy,” write Queen’s University Belfast academics Muldoon, Trew, Msfeti and Devine.

It is why those four academics pursued having a one-off question inserted into the Northern Ireland Life and Times (NILT) survey about flags (before those Belfast flag protests).

Unsurprisingly, the different communities in Northern Ireland responded differently. Those who identified as British and Northern Irish reported:

- hope and satisfaction in response to the Union Jack; and

- unease and annoyance in response to the Irish Tricolour.

These feelings grew as people’s self-reported strength of national identification grew, too: the more British or Northern Irish someone felt, the stronger the feelings of hope/satisfaction and unease/annoyance. When those who saw themselves as Irish were shown the Tricolour, their feelings of hope and satisfaction also grew in line with their strength of Irishness. However, interestingly, the same was not true when shown the Union Jack. They disliked it a lot even if they felt only a little bit Irish!

But very clearly, the respondents who saw themselves as British expressed stronger negative emotions than those who saw themselves as Irish or Northern Irish.

Apart from a few nuances, the research probably doesn’t tell us much we don’t already intuitively feel about flags, especially not after the last month. In academic terms, ‘intergroup emotions theory’ (which this research is consistent with) is well known to us in common sense terms of how we feel about where we fit in, and how we perceive the world around us in terms of safety and feeling unsafe. That we have strong emotions about the symbols that tell us which tribe is ours, and who’s not in it, are no brainers.

And yet, did any of the learning from Belfast’s flag protests shape either responses or public dialogue around this summer’s ‘Raise the Colours’ campaign?

We wanted to take a bit of a deeper dive into the research around what people really feel about their flags, because flags aren’t going away, nor are the issues which they symbolise. And if we know certain things – such as simply having flags around changes our attitudes and behaviour, without us knowing it – then we can make better choices in how we figure out who we are and how we want to live with each other.

Briton’s got flagitude

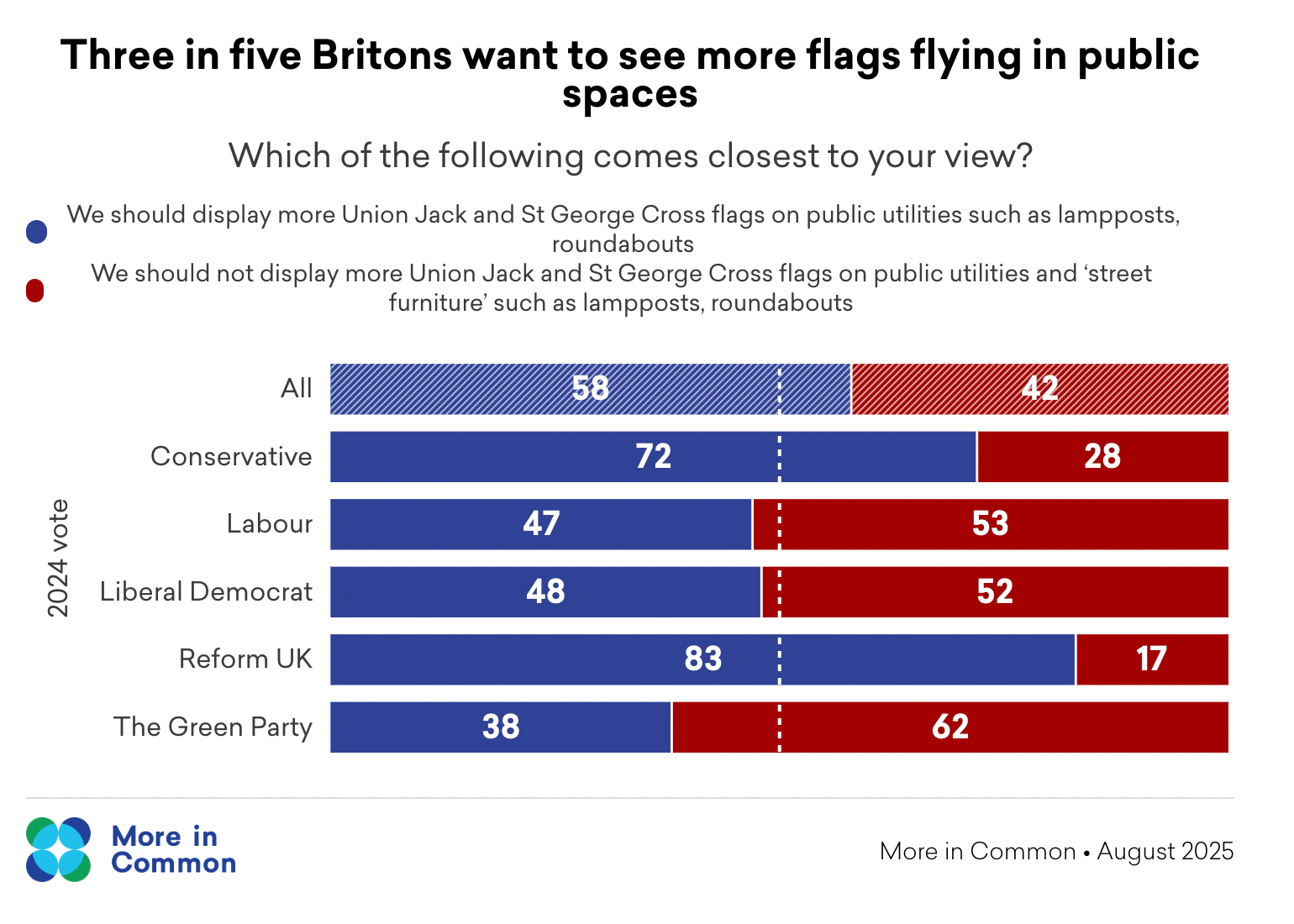

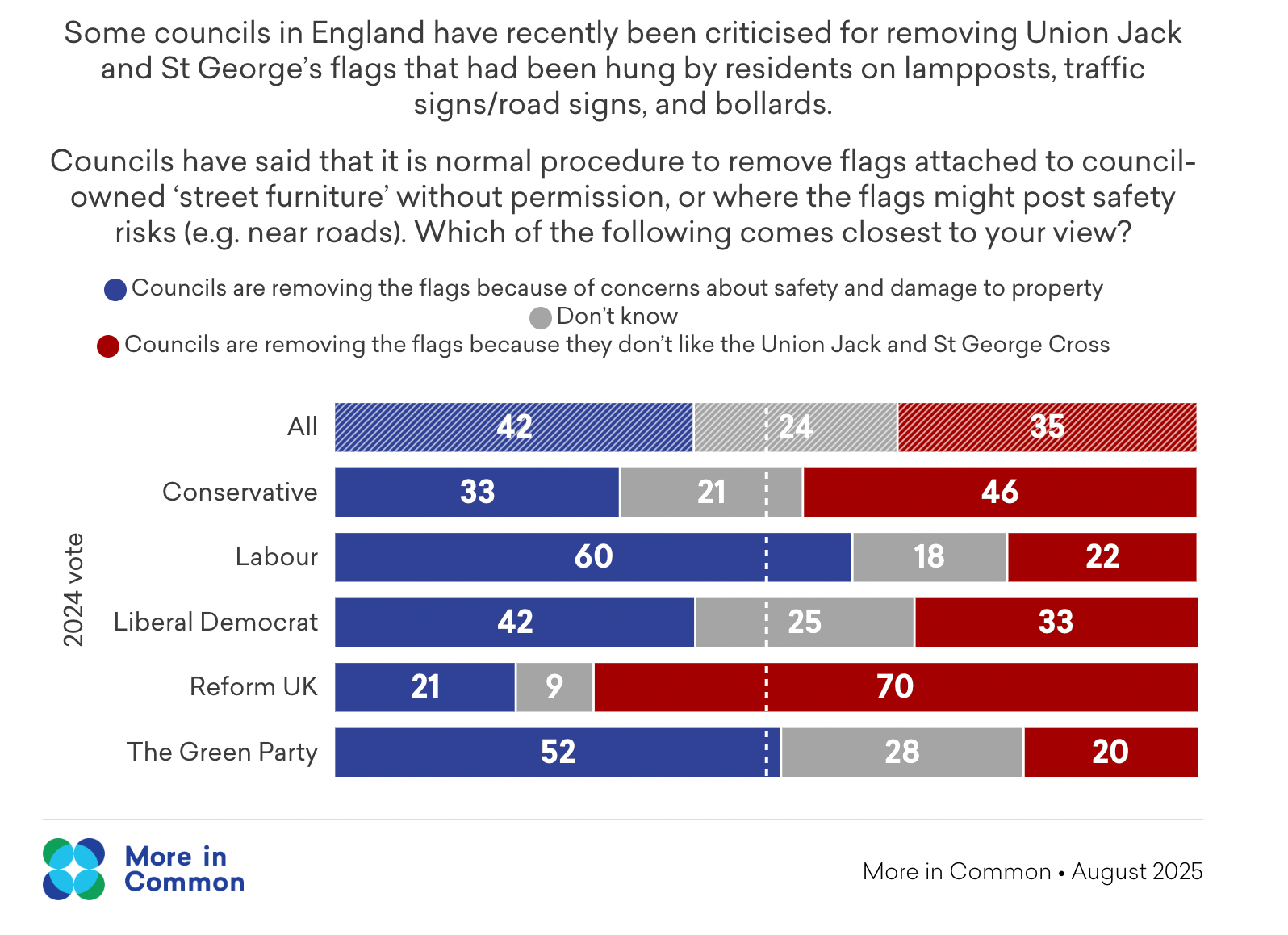

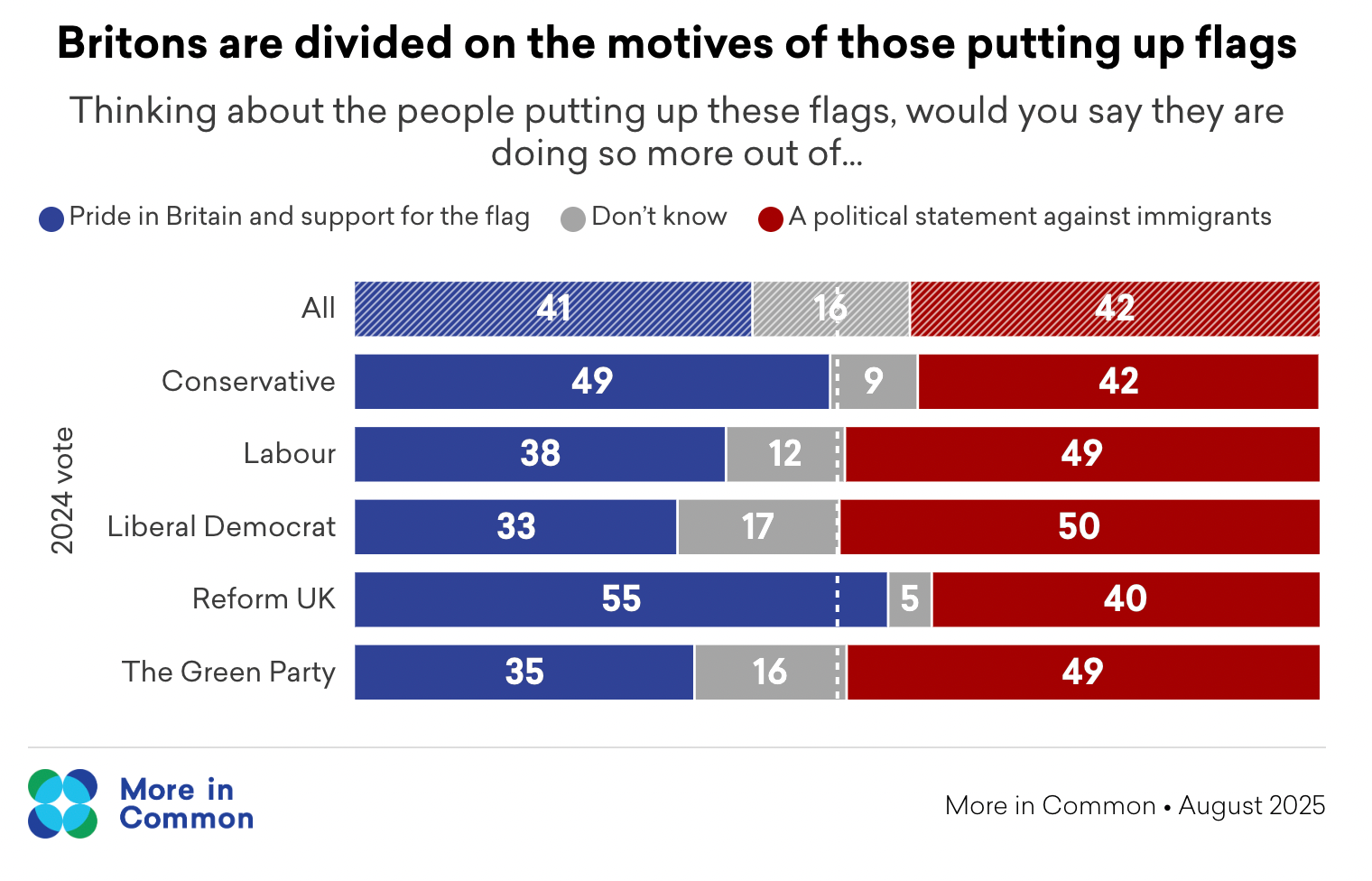

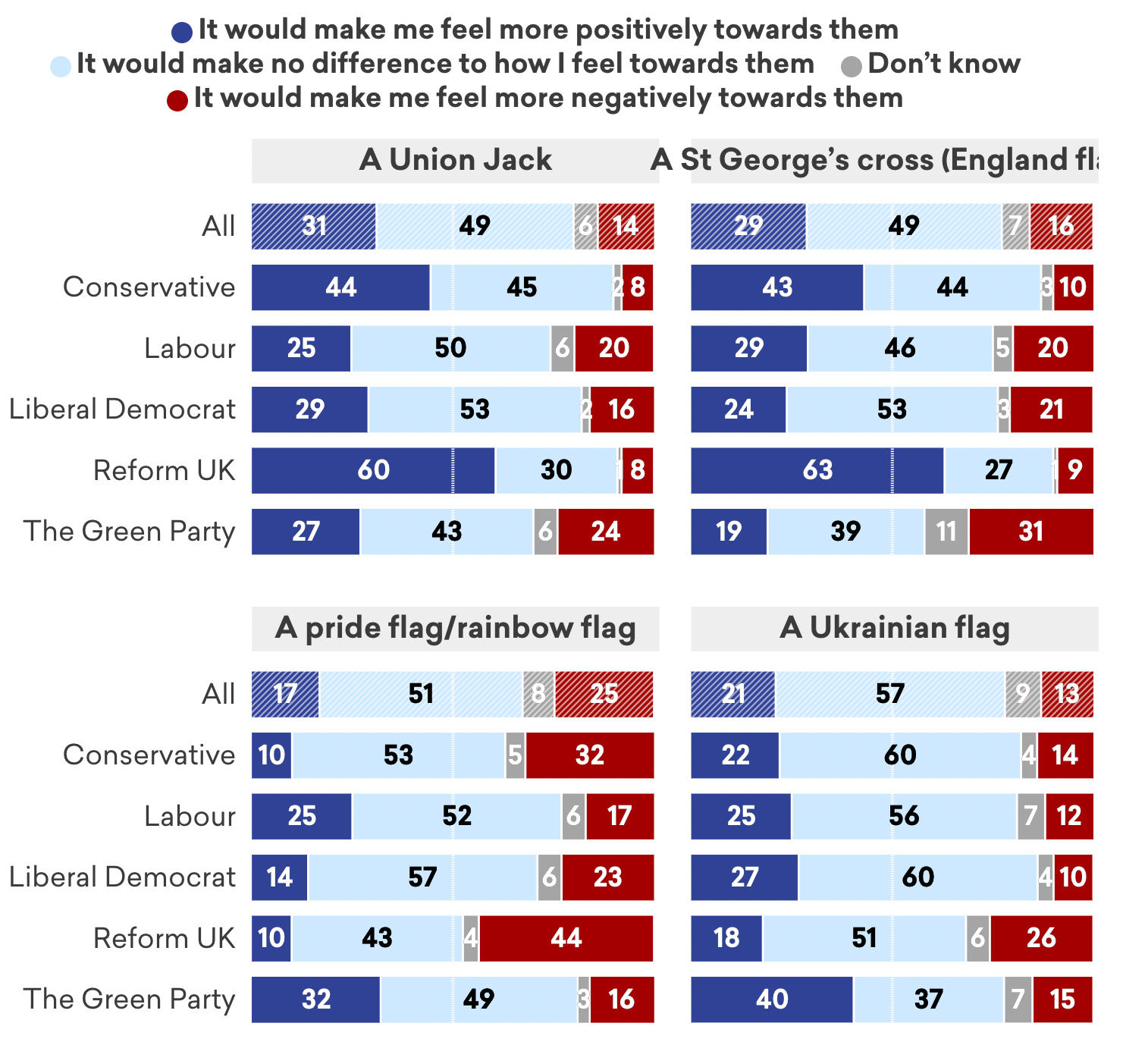

The most up to date (and trustworthy) figures on the attitudes of British people towards the flag debate were produced by More in Common in August 2025 in response to current events. These are the headlines:

- Most Britons (58 per cent) say that we should display more Union Jack and St George Cross flags on public utilities such as lampposts and roundabouts.

- Britons tend to believe councils are taking down flags for real concerns about safety and property damage

- Britons are divided on the motives of those putting up flags

- Most Britons across the political spectrum say they are unlikely to think better or worse of neighbours if they see them flying a flag.

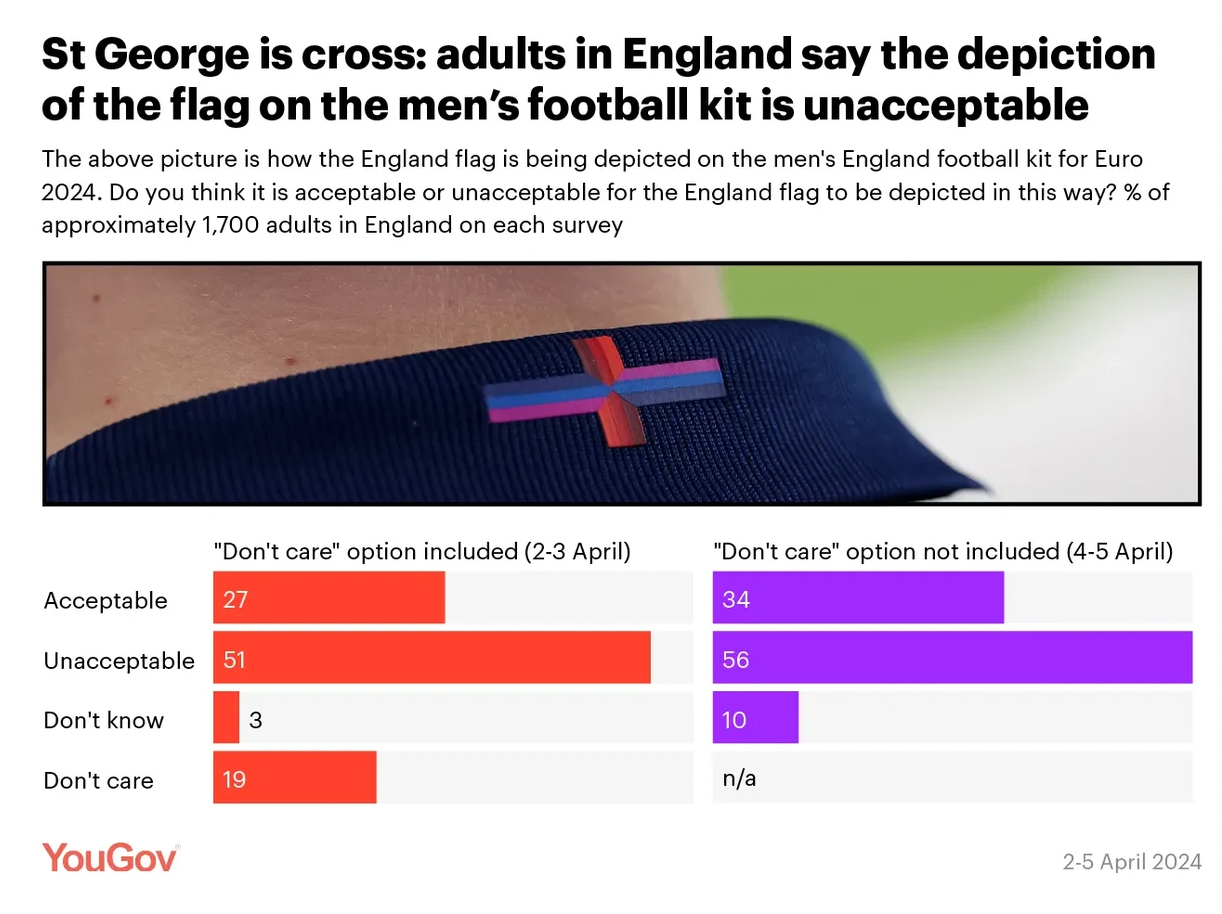

It would be easy to conclude from one figure above that a decent proportion of Reform voters are homophobic. But bearing in mind the symbolic gravity of flags as flags, as markers of difference regardless of what difference they mark, I’m not sure that ‘thinking negatively’ about someone because of a flag they fly transfers into such strong prejudice?

So 58% of people in Britain at least want to see more flags, even though (or because?) at least 40% of people think the flags are a protest against immigrants.

What this doesn’t tell us, though, is why the people flying the flags do so.

One position, made by expert Michael Kenny from the Cambridge Bennett School of Public Policy to CNN podcast The Curve, is that a “sense of disapproval, and the feeling that by flying the flag you are defying the norms of the governing system, is what makes it attractive to people wishing to signal feelings of disenchantment and frustration on issues like immigration.”

But it’s sometimes not as simple as we may think.

The American flag

American is perhaps the most ubiquitous and loaded flag, after the Union Jack, for its 20th century imperialism and the number of countries the US has bombed (36) since 1945. America has had a Flag Day since 1885. Every classroom in the United States will have a flag, and children are asked to pledge their allegiance to it as a matter of course (although this 11-year-old was arrested for refusing, as was his constitutional right). But who flies it?

Historical data shows that 55% of Democrats fly the flag, though more Republicans do.

In Northern Ireland it was the Loyalists, traditionally a working class grouping, who were at the heart of the Belfast flag protests; in the UK, the identifiers of Reform voters (most positive about flying either the Union Jack or St George flag) are those in poorer areas without degrees; in the United States, it’s people who have graduated with degrees who are most likely to fly their flag. Although age and race differences still matter: 67% of whites say they display the flag, compared with just 41% of African Americans.

A confederacy of…

Some Americans have a different flag though, of course: the Confederate flag. Research from 2017 looked at the emotional values that white southerners held for the flag, and found complexity there too, with four distinct sub-groups:

“Cosmopolitans, New Southerners, Traditionalists, and Supremacists. The greatest support for the Confederate battle flag is seen among Traditionalists and Supremacists; however, Traditionalists do not display blatant negative racial attitudes toward Blacks, while Supremacists do.”

And how about this: a 2008 study found that a 15-millisecond flash of the Confederate flag made white participants less willing to vote for Barack Obama than those shown a neutral symbol.

As we’ve discussed in the AI office and written about, what Fred Hampton did – sit down with Southern Confederates with their flags still flying – is not what people would do now, instead asking for the flag to be taken down or removed before sitting down to find common ground.

Cross-cultural attitudes

A 2015 paper that looked at 11 countries found quite significant differences in the emotions that citizens of those countries felt towards their national flag.

The only country of the 11 who didn’t have positive emotional associations with the national flag was Germany: mainly to do with the ongoing shame of the Holocaust. The exception was in sport, which was most German people’s conceptual association with the flag, as it was in Australia.

But then in places such as India, Singapore and Turkey, obedience was the primary association – in counties with more hierarchical and authoritarian social organisation.

Only in the United Kingdom and the United States was the main concept associated with the flag being that of power – because of imperial legacy.

And the country with least conceptual or emotional attachment to their flag (out of the 11 here anyway)? New Zealand. Although there was a pretty big debate about it when the Prime Minister tried to hold a referendum on changing their flag.

Jon Oliver on the New Zealand flag. Hat Tip to Tristan Clark for this beauty.

Don’t mess

And sometimes people just can’t mess with it – in certain situations.

Flags increase nationalism, not patriotism

The problem is this: there’s lots of research everywhere that shows exposure to a national flag changes your behaviour. And specifically, it increases nationalism, but not patriotism. (Where patriotism is defined as love and commitment to one’s country, and nationalism is defined as a sense of national in-group superiority over others.)

So flags do not increase love for one’s country.

But they do increase in-group superiority.

The problem is also that when flags elicit strong nationalist emotions with negative feelings towards people outside the in-group, especially anger, this is associated with action towards that out-group, often violent.

For example, last year’s summer riot attacks that led to many Black and Asian people being targeted.

It’s also clear that decades of research shows that feelings such as nationalism, as a set of emotions, is a driver of conflict and a barrier to peace. A study published in 2016 by social psychologists Callahan and Ledgerwood found that people perceived others as less warm and more threatening if the group was assigned a flag. “A consistent picture emerges,” writes David Smith, a psychology lecturer from Robert Gordon University in Aberdeen. “Flags bond insiders but make outsiders feel unwelcome.”

So if flags = nationalism and nationalism = conflict…?

Even at an International Scout Jamboree in Denmark, it was an unprogrammed flagging of a Palestinian flag that caused a moral panic, whereas the representation of Ukraine flags – white refugees; they’re like us – was no problem.

Or as Muldoon et. al wrote in their study of flags in Northern Ireland, “in contested nations, flags can divide rather than unite.”

Banal and mindless

The Union flag that flew over Belfast City Council was an example of what some experts have called “mindless flagging” or what Michael Billig called an example of “banal” or “everyday” nationalism. Until the empty flagpole led to it being very “mindful” indeed, even in its absence.

As another expert, Hanna Tange, has written, the shift from mindless to mindful, or from banal to significant, is often to do with context.

Wimbledon or football? Fine.

Terrorizing people in their homes? No.

As lots of people have written, it is the context of the flag debate – geographical, social and political – that has meant it has become so intense and divisive.

And yet the basic research shows that flags are such powerful symbols of “national togetherness” that they never exist outside of a context they bring themselves, affecting people subliminally and unconsciously: and often, to become more bonded with the in-group (your fellow English, straight people) and even more antagonistic to the outgroup (immigrants, gay people).

We’ve written about our use of flags in our design for the Fête of Britain. Is our divided nation best represented right now by a fragmented flag?

Perhaps this is why so many people do feel so uncomfortable with the huge increase in St George and Union Jack flags appearing on roads, roundabouts, and everywhere else – that we live in a contested country, where our story of who we are is changing.

And as we know, people do not like change (with other “lesser” primates being much more cognitively flexible to change than we humans).

Into the breach

One way we might think about flags going forward is to reflect on Kate Fox’s use of the concept of ‘breaching’ that she developed in her 2004 book Watching the English.

The breach is when something happens to upset our national sense of what should happen. So, in England – at least back in 2004 – when someone jumps the bus queue, or when the Cornish and Devonians get into a massive brawl on the Tamar Bridge about whether it’s the jam or cream that goes onto the scone first. Those are breaches of common English sense – and can cause serious outrage.

What we’re witnessing right now is that millions of people have a perception of England – and it is English people, mostly – being breached through uncontrolled immigration.

Their perceptions, which we also listened to on our Fête of Britain bus tour back in February this year, are that they don’t know who these new people are, being put up in the hotels, and that so many immigrants now aren’t willing (or able) to integrate. Snake-oil salesmen such as Matt Goodwin relentlessly amplify people’s fears. The fact that so much of the problems we face are created by the political and media classes, first of all not taking changing global population and movement issues seriously, and then using dangerous and ugly rhetoric and an incessant focus on immigration as a means to drive wedges between people as a means to take power, does not change the fact of people’s emotional situation; nor does it delegitimize real experiences and sense of loss.

What have we lost?

As was very clear in the testimonies gathered from the Belfast flag protesters, an overriding sense of loss was channeled through the flag, but expressed much broader perceived and felt losses around their lived culture under attack.

It is addressing these economic and cultural losses, while being fair to all those who come to Britain seeking shelter, safety, and work, that is obviously the challenge, wrapped up as it is inside the Multifaceted Intersecting Shitshow.

While we’re on the way to building a new democratic system and a better way to live, we can at least avert fascism, though.

At least the good news is that Britons do not currently feel more nationalistic than they have over the last 20 years. In fact, in Britain we are slightly less nationalistic (by 1%) than we were in 2019.

How do we then create more patriotism, as love and commitment, rather than nationalism, as superiority over others? What symbols, visual language, and practices can help us do this?

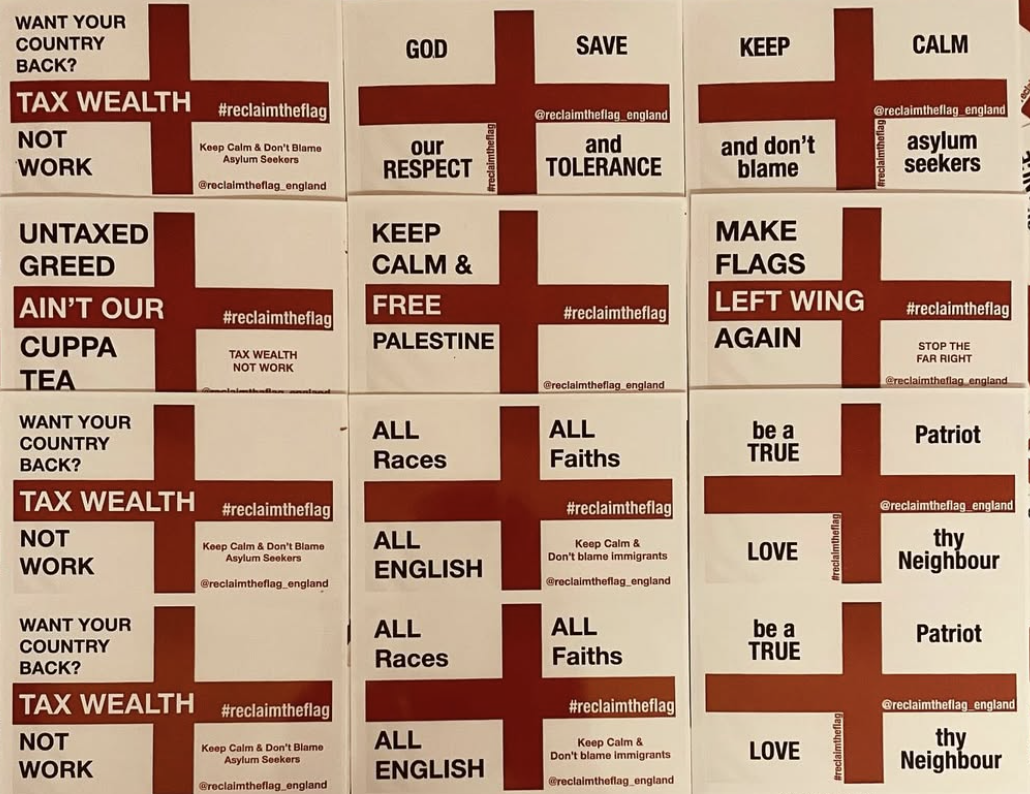

Maybe we can reclaim the flag for patriotism?

Or maybe flood the country with a million more flags of all colours?

Flags aren’t going anywhere, so how do we creatively and compassionately engage with the ways people feel about their flag? As Amit Katwala writes in a great piece for Wired from 2021:

A flag can be reclaimed, but it will require a movement of people willing to risk social status by going out on a limb and displaying what’s become a toxic symbol in some circles.

That’s something we at Absurd Intelligence have been relatively okay at: going out on a limb. Who’s with us?

Rough Trade Liverpool x The Fête of Britain, Friday 17th October, Hanover Street

If you’re in or around Liverpool next Friday, please get yourself along to Rough Trade x Fête of Britain for a brilliant night of music, talk headlines by Stealing Sheep, and more from local bands, artists and organisers, poets and printmakers, the legendary Bernie Connor, and more. The Fête is all about celebrating the neighbourhoods and nations we love, reclaiming pride in where we live, rooted in care and inclusion. Tickets here but they are selling out so be quick.

Elsewhere in Absurdity...

This week we have finally turned on the heating. In the wake of his sad passing at just 55, we are also reading or preparing to read 32 Words for Field by Irish writer Manchán Magan. But on the road...

- Clive and Charlie met up with their colleagues on the Foxglove Advisory Board. Big Tech, watch out!

- Sophie, Maddy and Charlie went to see brilliant feminist eco-anarchos The New Eves at their two-nighter at Hoxton Hall;

- David interviewed Nick Foster for the launch of his book Could, Should, Might, Don’t: How We Think About the Future at The Conduit;

- And finally, spotted at London College of Communication this week by our lad John, a Friday lesson for us all: