Love vs the Far Righteous

If the spiritual community can’t truly resonate with people’s lives, Christianity risks being co-opted by forces of hate and division.

This last week or two has seen a lot more column inches about Christ than most Christmasses, thanks to Tommy Robinson promising to ‘put the Christ back into Christmas’, his words prompting a wave of energy from Christian leaders reminding the public that Jesus was a refugee whose main message was to love one’s neighbour (including your enemies).

The same week saw the launch of Reform’s Christian Fellowship, with many Christians voicing dismay at it being hosted in a London church.

It feels a bit like a tug of war, with Jesus and Christian symbolism being grabbed by each side’s sense of truth and righteousness.

I find it a useful (if irritating and humbling) practice to try to see what’s true in what is being said by the person I disagree with.

And so with Tommy Robinson, I can see that he and I do have some common ground.

I generally find Christmas very difficult. Don’t get me wrong – I am fond of Quality Streets, appreciate the two weeks off work, and will well-up just from hearing the phrase “Merry Christmas, you wonderful old Building & Loan”. But I’m generally not quite sure what to do with myself – how to orient myself towards the festivities.

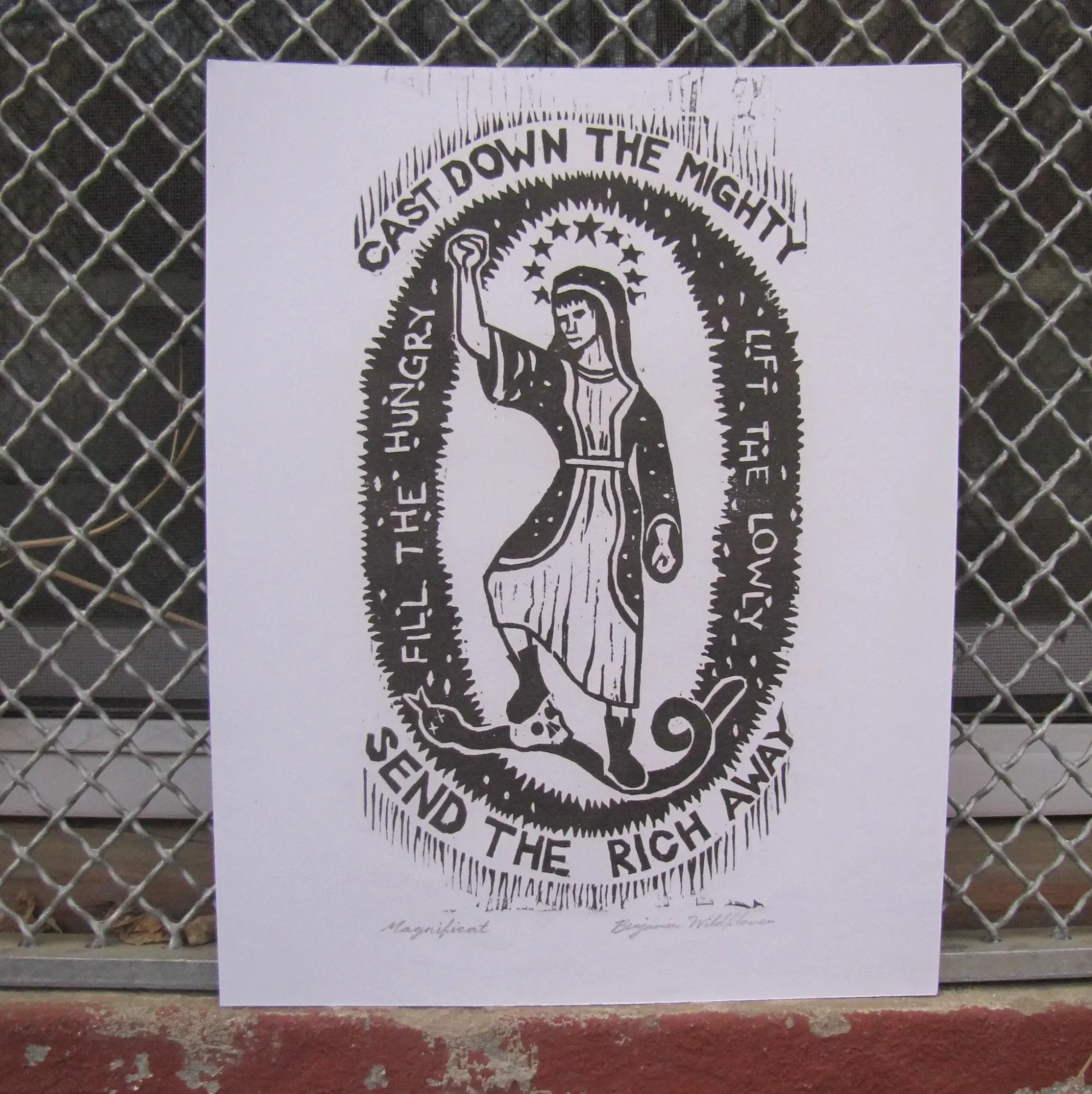

I don’t generally describe myself as a Christian; although I was brought up in a Christian family and I lead a church organisation, my own experience reflects that of many Unitarians, in that I don’t see Jesus as God. A powerful teacher, yes, but not the only teacher I turn to for wisdom. As such, when I try to engage spiritually with Christmas, it is at the mythic level – the Christmas story of the Bible being just that, a story, which can open up ideas of a better world, and remind us of the values we might hold. Part of my struggle with it is that for me, the nativity doesn’t seem like the most inspiring point of the story to pin the whole festival on (shift the calendar a little and let us celebrate the pregnant Mary’s radical dreaming with her cousin Elizabeth any day, as my friend Vanessa Chamberlin writes about so beautifully).

And what feels important to name is that although by most people’s standards I am a ‘Christian insider’, I can feel bewildered by and excluded from many church services, which often seem designed to make the in-crowd feel welcome, while not offering much of an entry point for outsiders who are new to the words, songs, and rituals.

I also struggle with the wider celebration of Christmas as led by those who don’t go to church, or pay attention to the teachings of Jesus at any other time of the year. The wild consumerism feels at odds with what I try to spend the rest of my life paying attention to, and it’s easy to feel disconnected from the shape of the celebrations: the noise, the plastic, the excess.

Since we’ve had a few generations benefiting from central heating and electric lights, the darkness of midwinter doesn’t quite justify the level of festivity. I’ve often thought we’d do better to move it back six weeks to February, when we really have had enough of winter.

What I think Tommy Robinson and I both feel is that there is something that has gone awry in our culture; that the values that are shaping society are not what they should be. That there is a gap where – possibly – there was once a more coherent sense of British (or English) identity, or a shared spiritual culture.

That’s probably the limit of what we agree on.

Part of the cultural unravelling that he and I both see – albeit from different perspectives and reaching different conclusions about it – do involve Christianity. By that I mean institutional and societal Christianity much more than the personal and community-level practice of faith. That Christianity has failed to remain relevant in the majority of people’s lives in Britain is part of the context in which – bereft of deep cultural meaning, belonging, and identity – people have turned to the likes of Tommy Robinson and Reform. Those qualities that could be found in religious community are now being offered by individuals with an agenda of division and hate.

Although I admire the speed, compassion, and integrity with which church leaders have galvanised a response to the co-option of Christmas by the far right, it doesn’t seem to have acknowledged that most Brits’ Christmases don’t have much Christianity in them anyway. It’s like there are two festivals called ‘Christmas’ that just happen to fall on the same date; one that is a minority interest religious festival, and the other a much more mainstream generic secular celebration. Just looking at the Church of England, 1% of the population go to a regular weekly service, and just over 3% go at Christmas. Meanwhile, about 40 million Brits will go to a pub or restaurant over the festive period.

I’m glad that the churches have stood up to show that the story of Christmas doesn’t belong to the far right, but the Christian Christmas they are protecting isn’t shared by very many these days.

At the recent National Emergency Briefing held at Methodist Central Hall, a gathering giving no-holds-barred truth-telling to MPs about the seriousness of the climate crisis, someone asked a question about the rising popularity of Reform and their position of climate denial. The response was that we must take responsibility for the deep inequality in Britain that has created the conditions for people to turn to Reform as an alternative to the status quo. It felt refreshingly, boldly honest.

I can see similarities here – that church leaders must take their share of responsibility for there being any credibility for followers of Tommy Robinson to lay claim to their values in Christianity.

If the church had already provided an accessible, authentic welcome, rather than overseeing decades of decline, the people now responding to Tommy Robinson’s call may not be feeling such a hunger, and would already be putting their energies into loving their neighbour, knowing that their neighbours include their enemies and those with different backgrounds to their own.

I’ve encountered plenty of people ruing the loss of Christianity in Britain who deep down are mourning a more explicitly patriarchal society, where everyone knew their place, that was more culturally homogeneous. I would guess that most of the people in Britain who don’t take part in church would see those ideas – Christianity and the nostalgic socially conservative ‘old days’ – as fairly interchangeable.

You have to get much further into the world of faith than most people in Britain get to, to know that followers of Jesus can be some of the most deeply radical, boldly caring, wildly inclusive people. Christianity’s popular public image tends not to portray that, and so the church can be seized on as a symbol of ‘the old days’ by those with no intention of loving their neighbour.

In some ways it’s no surprise that the Tommy Robinson followers seem to think Christians are fellow travellers with their ideas of social conservatism.

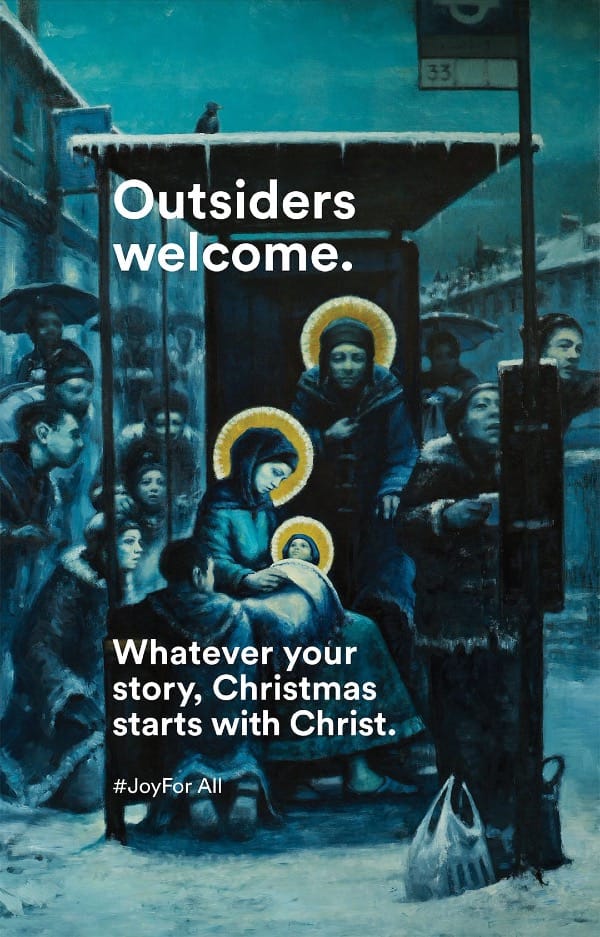

The short-term focus for churches must be to provide a genuine welcome to everyone this Christmas, just as they are, whatever their political allegiances (though not of course welcoming all behaviours). There is careful discernment in between the wealthy powerful leaders of far right movements and the lost and powerless who might follow them – discernment of who is to be cast down and sent away empty, and who is to be lifted up and filled with good things.

Longer term, it feels essential that churches show more clearly what they really stand for – shaking off both their fusty image, and their entanglement with the power and money of secular institutions.

For those at their limit of how much of the status quo they can tolerate, the church has an essential leadership role to play in demonstrating a world that is inclusive of all, that does give a home to the marginalised – whether they are refugees, the LGBTQ+ community, or isolated white working class people finding themselves without a coherent story of power or belonging.

What does it look like to offer spiritual community in Britain today that can draw on the teachings of Jesus, as well as the full depth of wisdom of all of Britain’s cultures, along with our sense of the divine in nature, and to do this in a way that truly resonates with people’s lives? If we don’t find a good answer to this question, Christianity will remain at risk of being co-opted by forces of hate and division.

The expression of ideas revealed by Tommy Robinson and his followers, however, are a part of the western society that was shaped by Christianity. They are not an aberration but a part of the whole. Christianity wouldn’t have got such a firm hold in Europe at all if it hadn’t been for its co-option by empire. Ever since Emperor Constantine pledged to put the Christ into Yule, there have been all manner of power-hungry leaders seeing that they can shape the story of Jesus into their narrative. As Unitarian minister Stephen Lingwood wrote back in 2020, Christendom IS white supremacy.

This is where we can easily get muddled – the far right might see their values written in Christendom, but at its best, the humble care that is often offered in the grass roots of Christian community doesn’t have much to do with empire. The powerful institutions that have shaped Western society might have done so in the name of Christianity, but quite often were also building up walls against outsiders, the poor, the marginalised. That former Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, could slide so easily from leadership in the oil industry to leadership in the church, doesn’t tell a coherent story of being in service to all life. (Perhaps incoming Archbishop Sarah Mullally’s background in nursing paints a more fitting picture of the humble work of caring for the vulnerable.)

What does it look like to shake off the patterns of empire and industry from all the good that can be shared from Christian teachings?

The way in which the church has responded to Tommy Robinson’s carol service gives me hope in pondering this question. Although many of the headlines proclaimed it as a ‘Church of England response’, the work was led by a wide mix of Christian leaders from different denominations – and it was done not by decision-makers at the top of a hierarchy, but by trust, relationships, WhatsApp groups and Google docs. There wasn’t a committee meeting, or a policy decision. People who cared called for help from people they trust. One of the initiators was my friend Al Barrett, a CofE vicar in Birmingham, whose recent Church Times article described the Church of England as the decaying carcass of dead whale – when something large is decomposing, it can provide nutrients for evolutionary diversity.

Perhaps that’s what’s giving me hope this Christmas – that in these times of widespread institutional decay, the ground-level trust and relationships can thrive in the gaps, learning from all of those who, like the radical refugee Jesus, have their attention at the edges.

Elsewhere in Absurdity...

This is the final Absurd Newsletter of 2025; dunno about you but it’s been a lonnnnnnnggggg haul! We can’t wait to return, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed after a couple of weeks of family, friends and films, ready for all the mischief we’re all going to get up to together!!

Thanks for reading our (hopefully not too garbled) thoughts over the past year, and thanks to everyone in the extended Absurd Family who have written pieces for the newsletter.

Amongst the Christmas celebrations (Foxglove, Nerve, Byline and Hard Art we love you all!!) we’re still squeezing-in some extra-curricular activity.

Wearing his hat as Founder of The Atelier of What's Next, David has been working with the Sustainability Accelerator at Chatham House on improving decision-making in the face of The Rift from the past status quo to whatever tomorrow holds. The concept: a new AI-enhanced approach to horizon-scanning and creating fragments of radically different futures. A first workshop has provided proof of concept. Now into the next phase.

Oh, and Sophie’s off to Stonehenge for the winter solstice. That covers just about everything!

See you in ’26 xx