The Work is Love

Part two of a birth-and-death double-header, and the Freedom that is utterly bound-up with Care.

I lost my mum over the summer. In clichéd platitudinal terms it was a good death. An innings of 93; all marbles present; independent to the last.

She spent her final three weeks in St Wilfred’s hospice in Bosham, a sleepy Sussex coast village.

Bosham’s church is the only English building apart from the White Tower (of London) to feature in the Bayeux Tapestry, Harold having popped-in to worship en route to Hastings. In front of the church an eerie no man’s land mudflat harbour is where King Cnut is said to’ve sat in his chair to prove his very un-divine inability to hold back the tide.

Such seismic British history – the OG invasion story (and in the Normans, the beginning of the end for the English commons), and an environmental metaphor for the ages were ever-present on my bedside-breather walks around the village. My mother’s arc was a blip in comparison, yet she witnessed ten decades where such history folded-in on itself.

While never quite working out what it was I did, she had become a late convert to environmental matters. Not one of the chain-me-to-a-railing Extinction Rebellion grannies exactly; more of a quiet cheerleader. She would often remark on the ridiculous trajectory humanity had taken in her life: the arrival of widespread commercial flight, rabid consumerism, the destruction of town centres built around community. She clearly remembered the day her own mother had come home from her first visit to The Supermarket, professing it a miracle! No need to visit all the different shops any more!

All this innovation had arrived in her lifetime, and my mum could see that – in the span of a single life – it needed to go away again. Thank god she never had a computer. Or smartphone.

A war child, evacuated twice, yet still somehow in London for both The Blitz and the V1s, she maintained that rationing had made hers the healthiest generation. Hers was also the last generation to’ve seen how a nation can totally transform itself when failure to do so would mean unimaginable hardship. She voted to Remain, not because she was a metropolitan traveller (as a kid, the only foreign countries we went to were Ireland, Wales and Scotland) but because she’d witnessed what happens when Europe falls out with itself.

So she was tough. A survivor. Definitely someone who was going to be in control of her own life for as long as possible. My mum had never wanted to give in. Never wanted to admit defeat. Keep Calm And Carry On could have been her actual, unironic motto. She was the very epitome of Business As Usual, definitely – definitely – not going into a home. Or seeking help.

And then she had to.

Until a week before everything changed she had still, unbelievably, been climbing stairs – suddenly, she was barely able to get up from an armchair, a situation that was simultaneously ‘fine’ and quite obviously not fine.

The first of an amazing set of human beings from St Wilfred’s home-visiting community team suggested that my mum might benefit from a couple of days of respite care. “Just to sort out the medication.” It was exactly the bridge my mum needed. A noncommittal invite that allowed her to accept help.

I’d expected push-back. My mum had experienced a rough three months in hospital about seven years ago, the latest in a life-long series of suboptimal brushes with the medical world. (For example, I had been born by C-Section, and the anaesthetic had been mismanaged: it paralysed but didn’t anaesthetise.) After that rough three months, she was even more committed to staying in her own home.

But, once at St Wilfred’s, my mum said four utterly uncharacteristic words when I first asked her how she was finding the hospice. “I feel safe here.” In one short sentence, we both knew (of course we knew) that this wasn’t respite, but release.

I realise as I’m writing, that this is hardly rocket science. Sometimes people need permission, need help, need guiding – in death as much as life. What I encountered, what my mum experienced is hardly new – there are no insights of cosmic truth being unearthed here. Yet the love and kindness, the care and freedom deployed in this small Sussex hospice still came as a revelation.

The chef who cooked special food even though it was obvious she wasn’t going to eat. The name on her door that was changed when staff realised she liked being called Bobbie, not Barbara – even though she wouldn’t see it. The Cinnamon Trust dogwalkers who set up a chat group to make sure that there were visitors morning and afternoon, and that Lulu, mum’s equally-aged dog, could visit twice a day.

We are so used to the ‘everything is broken’ story that when compassion catches you as you fall, it does so unawares. Every single person in St Wilfred’s, from cleaner to consultant, held my mum’s last days with a clarity around one hitherto secret fact: it is OK to die.

__

As my brilliant Absurd Accomplice Nuala wrote last week, there is a world of care, encountered on the basis of need.

Through pregnancy and childbirth I happened upon a world of (mostly) women who understand something that our society marginalises, but is totally dependent on – care, birth, transition and transformation. How hidden this world of midwives and doulas is unless you work in it or until you depend upon its care.

Hers was experienced at the start of a life, mine at the end, in the same balmy mid-August week. Both of us simultaneously reflecting on fundamental life events in the context of where our day job heads and hearts are at.

How different would our world be if, instead of remaining out of sight in the wings, the doulas and carers, the nurses and midwives were at the centre of how we navigate life? And I say this not in a naïve oh-can’t-we-all-just-be-nicer sense (although, why the fuck can’t we be that too), but because of (as Nuala says) the transitional power we would place at the heart of society.

So many people declaring the world needs to change, yet those in positions of power who might be able to get on with it refusing to. The evergreen Gramsci’s “the old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born” sounds like a cry for help, a bat sign shone to call the folk who help end the stuckness before both death and birth.

We need an army of Care to help us collectively say “I feel safe here” as we make decisions to take the action our world requires. Transitional navvies to build dignified routes by which we might all surrender.

I’m the world’s least qualified person to be writing this kind of stuff – Hospicing Modernity and At Work In The Ruins glower at me from The Pile Of Unread Books. I know they exist. But I do also understand the concept of composting, and that The Shitshow is real.

__

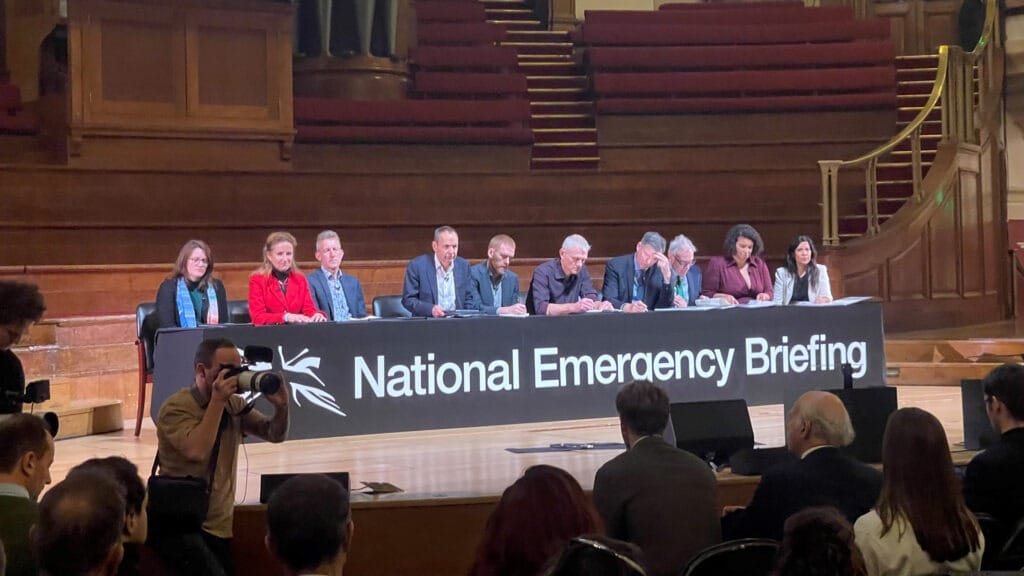

Last week’s National Emergency Briefing appeared to be stuck in a politics-as-usual paradigm of persuasion by profit. Perhaps it was a tactical decision, focused as the briefing was on talking to MPs, but there was an abundance of ‘pay now, not later’ logic. An ROI-driven narrative where future returns are deployed into a landscape filled with battalions of bad actors, brown envelopes and politicians so short-sighted they cannot see beyond ‘pay now’.

It seemed a world away from sleepy Sussex, and the people who spend their days in service to dying. Washing, dressing, mopping-up; talking, holding, making tea. It took two of my mum’s last three weeks for the hospice to make a decent cuppa: two teabags the secret, it turned out.

Don’t get me wrong – there were brilliant people saying brilliant things in Westminster, and the struggle we’re in needs everyone, everywhere; it looked great too, proper official. My mum would definitely have resonated with Prof Nathalie Seddon’s speech on Nature, and Richard Nugee’s wartime mobilisation rhetoric (bring back the ration card!).

But I couldn’t shake similar thoughts to those I had staring out at brackish Bosham Harbour.

We have to corral the caring, decent, ordinary (yeah, I know people hate ‘ordinary’) people who live far from the bubbles of power and politicking. Not to stand in support of ‘compelling argument’ or ‘irrefutable logic’, or to cheer for those who know the score (as the assembled briefing speakers obviously did), but to collectively roll up our sleeves and get on with even more of what is already happening.

To do the work of love that might just help us all cross over. To let the old die and new be born. The work that doesn’t shy away from pain and hurt and tears, because we none of us have been born without all of those things, and we won’t die free of them either.

The astounding human beings that entered my family’s life as my mum was leaving understand this, as Cnut understood the tides. The people who helped Nuala’s beautiful baby girl into the world too.

The work of Care is the work of Freedom.

And The Work is Love.

Elsewhere in Absurdity...

We hope you’re showing yourself some love at the twilight of the year. There’s a lot of exhaustion about; many are maxxed out. Let’s all go and immerse ourselves in the ‘Bosham harbour’ where you take your breather. Elsewhere...

Last Friday Alex, Jess, Charlie and the crew delivered the second Good Neighbours show, a livestream shining a light on the arts, culture and community organisers who keep this country running, doing the work of love where they live. Please have a watch and subscribe for when we’re back in 2026.

David was at a meeting of the Centre for Understanding Sustainable Prosperity, an academic institute which asks ‘What can prosperity possibly mean in a world of environmental, social and economic limits?’ and works on subjects as diverse as theology, flow states, forests, and youth action in the Middle East.

Charlie was on a Hard Art panel at the amazing multimedia show Nine Earths at Westminster University (and is off to recce Manchester to recce for a Spring Fête of Britain!).

And on Monday Charlie and crew were at the most recent instalment of Hard Art, where they heard from, among others, the incredible Darren Cullen.